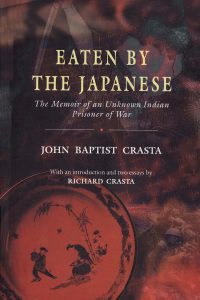

Exactly 20 years ago, on October 8, 1999, my father John Baptist Crasta, former Prisoner of War, author of a war memoir, and father of four children, breathed his last in the S.C.S. Hospital, Mangalore, India. In his army career, he had seen action in Singapore and Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, besides Papua New Guinea, where the Japanese held him prisoner for 3.5 years.

His war memoir, written in 1946, a few months after his liberation from his Papua New Guinea prison camp, lay in his steel trunk, unpublished for 52 years until I published it under the title “Eaten by the Japanese” in 1997 Dec/1998, less than two years before his death. The book (available on Amazon, Apple, Google, etc–but not Kobo, possibly because it is Japanese-owned), has moved many readers in many different countries, and was also published in Singapore by Raffles Editions. And now I must briefly tell the story of his last years, because I cannot put it out of my mind.

John Baptist Crasta had escaped the Japanese; he had survived 3.5 years of brutality, starvation, disease, and bombing. He returned to India, ecstatic at being reunited with his mother, who had worn the black sari of penance and widowhood, kneeled on a rock, and prayed for him all through his captivity. On return, he looked like a shattered man, with what we would now diagnose as PTSD or Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome. To recover his health, he was sent back to his family in Kinnigoli, and during that time, he wrote his memoir, as if confident that the past would never repeat itself.

In a way, it didn’t, for over 30 years as he married my mother and raised four children, sometimes in good postings, like Bangalore and Calcutta; sometimes in hardship postings, like Panagarh and Bareilly; and in a way, it did. In his last years, he again went through a period of darkness, until he died ten days after admission to the hospital for a broken hip at the age of 89.

My father was a gentle, softspoken, stoic, and kind soul; he was the one who, in a house where food was not abundant, took a precious piece of meat from his own plate and fed it to the dog, his heart filling with love and happiness as he watched the dog grab the meat and gobble it up, his tail wildly wagging. He also never denied a piece of fish from his own plate to the domestic cat (which had somewhat more freedom of movement in the house). In poorer households in India at the time, dogs and cats received only rice, bones, and semi-edible meat and fish leftovers, never the pieces of meat or fish that a human might conceivably consume.

Did I do enough for him, I ask myself. Then I note with satisfaction that his memoir is still being bought and read 20 years after his death. Here is a section of a Preface from an old edition (pardon the formatting errors; some corruption from an Indian font, Shruti, sister of Latha, crept in, and I have cleaned up some of it manually: would welcome any savvy reader letting me know if there’s a faster way of doing it.)

The Man on a Bicycle

John Baptist Crasta Prabhu—whose son I claim to be in more ways than one—was born on 31 March 1910, in Kinnigoli, a nondescript village where nothing has, does, or ever will happen, a village whose only virtue consists in the fact that it has a road connecting it to the larger town of Mangalore, a port in the quieter, monsoon-drenched Southwestern section of India where little of earth-shaking importance has happened since the beginning of time, and where in the early decades tigers still roamed the villages and town borders, snacking on animals and people. He was the firstborn of eight children, the others being Lucy, Antony, Aloysius or Louis, Ignatius, Bonaventure, Margaret, and Gerald. Make that eight thin children. “We came from a family of thin people,” said Uncle Louis recently, himself pretty thin despite ascending in mid-career to the world of medium-fat cats.

The Crasta children may have been thin in body, but their lives were thick with rosaries. “No rosary, no rice,” was their Mater’s domestic dictum, her inverted version of “No taxation without representation.” Religious fervor was common in these descendants of Konkani converts to Catholicism who had migrated from Goa to escape the Portuguese Inquisition a few centuries earlier. But here, in a British province long used to paternalistic rule, in a country where life was nasty, brutish, and often cut short by snake bites and other gifts of nature, the Catholic priests continued to exercise power over their flock, threatening hell and damnation to sinners and moral stutterers. “They were dictators,” said the late Dennis Britto, a raconteur and freelance social analyst who spent most of his life in an easy chair (a reclining chair), delivering sermons to whoever was around.

My father remembers his own father, Alex Dominic Crasta, an only child, mainly as an invisible father, absent in soul and body, working and living an inaccessible seventy miles from home in the mountainous jungles of the Western Ghats. Though Uncle Louis, whose memory seems in better shape, remembers Alex Dominic as a non-drinking one-time owner of four or five gadangs or toddy shops, my own father seems more underwhelmed or hazy about him. His childhood, he maintains, was shaped by his mother. “My mother, my savior,” he characterised her recently in a quavering voice while gazing at her photograph, tears forming in his eyes.

Her name was Nathalia, and she was both a housewife and a provider. She would feed all her children first, and then eat the leftovers, if any (a not uncommon habit among Indian mothers, for I remember my own mother doing the same). Nathalia and the family had faced two tragedies even while my father was a child. **One day, as she was massaging Baby Louis, her two-year-old second son, Antony, had fallen into an open well and drowned, despite her having jumped into the well to try to save him. Later, still another son, Ignatius, had succumbed to the bite of a rabid dog, there being no effective medicine for rabies at that time, at least none accessible to the indigent citizens of Kinnigoli.

“He was sado—simple and straight, never talked ill of anybody, never got into fights,”my uncle Louis says of my father. When it came time to attend high school, my father walked the twenty miles to Mangalore, over hills, through roaring streams and patches of jungle, stopping at the “big houses”—meaning, the houses of the well-heeled—for a little free refueling, a glass of water and a piece of jaggery to revive his flagging energy. He found himself a room as a private boarder in Mangalore while attending Saint Aloysius College High School. One day, when his mother heard that he was sick, she took his baby brother on her arm and walked the twenty miles to Mangalore to see him, being too poor to afford the bus.

It is harder for a rich man to enter Heaven than for a camel to enter the eye of a needle (or for a rich man to enter the eye of a camel too, perhaps?), or so the Bible says; but it was always pretty easy for a rich man to enter St. Aloysius College and its high school, and to escape the whipping the padres gave to the fiscally and morally **unlucky. After all, the college towered over property donated by the local squire, the college chapel drawing the town’s unwhipped cream of society which disdained to grace their own parish churches polluted by the hoi polloi. My father, though by no means a member of India’s wretched poor, belonged economically to its struggling lower middle class. And often, because he had not paid his two-rupee monthly school fees on time, he was kicked out of his St. Aloysius High School classes by the Italian Jesuits, the highest official representatives of Jesus Christ, Friend of the Poor.

When he was once again late with his school fees, the priests, under the guidance of Bishop Perini, the Italian-born local prelate, wouldn’t allow him to take the high school final exams. Dejectedly, my father walked the twenty miles home to Kinnigoli and told his mother his story. She interceded with the local parish priest, Father J. L. Pais, a man with a rich heart. The good padre lent her the money, and my father obtained his diploma.

Mangalore still being a one-hundred-bullock-cart, seven-Model-T-Ford town with limited employment opportunities, the **high school graduates would head for the nearest metropolis, Bombay, to find a job. Thanks to the invitation of a family friend, Ignatius, my father hopped on to Karachi instead. He would go on to become a well-travelled man, though over three-quarters of that mileage was forced upon him either by the Army or by the Japanese. After five years of assorted labor in Karachi, he joined the Army in 1933.

A year later, he learned that his father had died. My grandfather had caught pneumonia and was quite ill on Easter Sunday, 1934, when it was decided to take him to the nearest hospital in Mangalore twenty miles away. The mode of transportation? The bullock cart of a friend. However, the cart’s owner did the Christian or Mangalorean Catholic thing: he decided not to miss his Easter revels of booze and delicious pork and mutton curries. Festive meals, which occurred about four or five times a year at Christmas, Easter, the parish feast, and wedding celebrations, were not to be sneezed at. It was nightfall before the cart started for Mangalore with its human cargo. When it reached Father Muller’s Hospital the next morning, Dr. L.P. Fernandes lifted the sheet, checked my grandfather’s pulse, and said, “There’s no point admitting him. He is dead.” My grandfather’s body, having joined The Dead shortly after the time that his friend celebrated Jesus Christ’s rising from it, was upgraded to taxi class on the return trip to his Kinnigoli graveyard.

The death was a blow to the family, especially because widows suffered a steep fall in social status and other inconveniences at the time. Also, in the absence of income, the coffee estate land that Alex Dominic had been sanctioned reverted to the government for nonpayment of dues. My dutiful father, who had already been partly supporting the family, now lived even more frugally, sending all his savings to help support his mother and younger siblings.

For most of his adult life, except during that interval when it was punctured by the Japanese, my father’s main mode of transportation was a one-gear bicycle so basic and close to the original invention that its only accessory was a bell. He was our man on a bicycle. He rode a bicycle in the sun and in the rain, in the day and at night, a “market bag” containing fish or vegetables usually suspended from its handlebar. Nothing could persuade him to abandon this humble vehicle, much scorned by Indians obsessed with middle class respectability, for a loftier mode of transportation: not the possibility that he might puncture the ballooning ego of his son the Indian Administrative Service officer, not an improvement in his financial position late in life, and not even his children’s offer to pay for his autorickshaw fare or to buy him a scooter (we really couldn’t have afforded to buy him a car) after being provoked by the taunts of relatives. He rode his bicycle till he was seventy-six years old, whereupon he visited the United States for four months to visit his emigrant expatriate son, and realized upon return that two culture-shocks—the first on reaching the United States and finding trees near JFK International Airport instead of the endless skyscrapers he had expected, and the second on returning to India after four months of two-wheeler deprivation—had rendered him incapable of resuming his bicycling career.

I mention these details simply to underscore the simplicity of the man, the humble position he occupied for most of his life, and the fact that life was not very kind to him except in granting him life and allowing him to cling on to it for almost as long as was legally permissible for a resident of a country where life doesn’t count for much: given that its possession of the world’s second largest population—or one-sixth of the total—does not even entitle it to a permanent voice in the United Nations Security Council. The bicycle, which at first had been an economic necessity, grew into a rusty, creaky, yet indestructible symbol of his contempt for the shallow status-consciousness of Mangalorean society, where upperclass persons living just next door to the church would drive the hundred yards to get there rather than risk the shame of being spotted walking like the not-blue-blooded middle class—who in turn would walk long distances rather than endure the shame of being spotted on bicycles, the transportation of the decidedly lower middle or janata class.

Mangalorean upperclass society returned his contempt with compound interest. The callous Plymouths, Fiats, and Ambassadors of the rich drove dangerously close to him, often making him scamper off the road onto a stone-littered sidewalk to save himself. And yet, I mention the bicycle only as a symbol of his modest, unhonored life. If it is true, as the nuns and priests told me when I was a child, that God showed his special love for certain individuals by sending them especially large gift-parcels of suffering, then God loved my father a little more than He should have. Indeed, God loved John Baptist Crasta so much that he sent him suffering, suffering, and more suffering. John Baptist Crasta was baptized in suffering—and rebaptized, and baptized again. (And some of these baptismal gifts are known only to family members, and may have to remain private.) Indeed, the Crasta family itself must be a hot favorite with God.

Luckily, it was not just God, but Life, too, which must have had a soft spot for my father, for he survived it all, and saw many of his social, financial, and military superiors to their graves.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, I am proud to present to you my father, John Baptist Crasta, the author on a bicycle.

In addition to the first Indian/U.S. editions, Eaten by the Japanese is available in paperback in 2 new Amazon paperback editions,

2012 first edition, and a

besides these e-book versions: