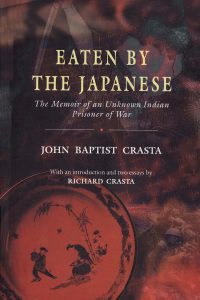

March 30, 2020: One score and zero years ago, my father’s World War 2 prisoner-of-war memoir, Eaten by the Japanese,** had its official national launch at the India International Centre, New Delhi (along with the launch of the U.S. edition, which was the same paperback product, except for having U.S. ISBNs on the copyright page and the price in dollars on the cover). It had a stunning cover, the gift of an artist whose name I have forgotten (apologies, please contact me if you see this).

At the book launch, I was surprised to notice Dhirendra Singh, the Additional Defence Secretary of India at the time, in the audience. I don’t know how he heard of my book launch, but I was delighted that he came, and I will never forget that he purchased 5 copies of the book, and insisted on paying the full price for them. This is the kind of classy behavior that authors never forget, not even when they are rich and famous, if ever (and the chance of that happening, for any average author, is around 1 in 25 million; for me, one in 500 million).

Why did I recognize Dhirendra Singh, and why did his presence matter so much to me? Because Dhirendra Singh was one of my first bosses, and probably my finest boss ever: he was Deputy Commissioner of Hassan District in Karnataka State when I was posted to Hassan as an Indian Administrative Service Probationer for district training. Tall, with a thick and drooping moustache; round-faced, and with a mildly diminishing hairline (I think), Dhirendra Singh had gracious manners, had spent some time in England (sent by the government for training), and was an avid reader. He had a wry sense of humor, and spoke softly, which meant I couldn’t get half of his witty remarks, which flew past me as Hassan’s famous mosquitoes did.

This was the time when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had declared a state of emergency to ward off Opposition challenges (much like Trump has been considering doing in the US), and the Deputy Commissioner was a very powerful man (or woman, in rare instances at the time) who could order the arrest of someone under MISA (the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, not infernal security). But he wore his power lightly, unlike the Deputy Commissioner who reportedly ordered the arrest of a young but poor man who was in love with his daughter and dared to try to reach out to her. Dhirendra told me he was ordered by higher-ups to arrest Deve Gowda, the future Prime Minister of India, and a man he respected, and that he had apologized to him for arresting him (this is what I remember, and I can’t say my memory is bulletproof, and I have faced too many bullets in my outwardly pacifist life). In return, Deve Gowda never bore any grudges against him, but on the contrary.

In Hassan, once called “the poor man’s Ooty” (a label that has also been applied to Mysore), Dhirendra lived, along with his gracious wife and two young daughters, in a bungalow situated in a huge compound with massive old trees (many Java fig trees, rare in India*), which were the preferred recreational center and hangout for the swinging monkeys of the neighborhood.

Dhirendra Singh went on to become Defence Secretary of India (rather appropriate for his name, which translates as “brave warrior”) and then Home Secretary, which was probably the second most powerful job in the Indian bureaucracy next to the Cabinet Secretary.

Eaten by the Japanese has probably sold around 1500 copies worldwide (cumulatively, in many editions, including e-books), but its influence has been slightly more than its modest sales might suggest, because it has been examined and commented on by scholars in scholarly papers, and has received glowing reviews. And for me, this has probably been the most fulfilling project ever, since it was a gesture and offering of peace to my father at a time when he was only a year and some months away from breathing his last breath. Thanks to Dhirendra Singh, I was invited to meet General V.P. Malik, the Chief of Army Staff, who not only greeted me with warm courtesy, but expressed a desire to pay a visit to my father—and, when informed, to his disappointment, that my father had passed away the previous year—to meet my mother. That didn’t happen, because he retired shortly thereafter, and probably was too busy to schedule it. I also met George Fernandes, an ex-Mangalorean Catholic who had climbed a seminary wall to escape padrehood (and possible future Popehood) and run away to Bombay, thus beginning a dizzying climb up the political ladder to become the first ex-Mangalore Catholic Defence Minister of India. Fernandes impressed me with his babysmooth skin (zero wrinkles, despite being in his sixties, possibly) and ultimate cool. Dhirendra Singh also passed copies of the book to other senior army officers, some of whom told him the book brought tears to their eyes.

One of the biographical and personal essays that I added to my father’s book, titled “The Man on a Bicycle,” (but now titled as “Invisible Beginnings” or “Fathers and Sons”) so touched my own son, James, that he became a devout and humble bicyclist in his teenage years, and has continued to bicycle around wherever he went, to study or work, and now does in Colorado for leisure. It was only a few years back that James confessed to me how much that essay of mine, on his grandfather, had influenced him, and how much he admired him. Over the years, I toned it down somewhat, but am now considering bringing out a special edition that is uncensored—because the passion I felt at the time is partly the reason for the book’s existence in paper and e-book formats, and its availability with at least ten major retailers worldwide, though not in a regular bookshop.

But the amount of time I have spent over the 23 years I have spent producing and publicizing it, and all the “No”s I recceived from Indian book distributors, all the copies that lay in warehouses gathering dust and disintegrating and disappearing–it would discourage and dishearten any would-be publisher … unless you were convinced, as I was, that this was a sacred mission, an act of self-redemption, one for which no sacrifice would be too great.

[As I publish this, three COVID-19-fraught months after I wrote it, it’s closer to V-J Day or Victory in Japan day, which would be around 75 years from the time Japan surrendered, bringing an end to World War II, and to my father’s liberation, and possibly saving his life. Though Japan’s surrender was announced on August 14, the Japanese only informed my father on August 19–thus denying him and thousands of Indians five extra days of happiness. And yet, a few months later, he wrote what is probably the only surviving Indian POW memoir from World War II.]

*Description of Java fig tree from Dhirendra Singh: “They grow to great heights and cover a lot of space . One of the biggest I saw was the one in the Kandy Botanical Garden in Sri Lanka . Actually within the grounds is a historical building . It was the SE Asian Military head quarters of Mountbatten in WW2.” Thanks to that Java fig tree, we are all connected–Mountbatten, I, and the intrepid swinging simians of Hassan.

**By now, several other revelations (including one of George H.W. Bush’s escape, and a report in the Times of India) confirm what my father wrote about: that POWs in World War II were sometimes used as food.

Book available at:

https://richardcrasta.com/buy-books-direct/

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B004UBFXFC

http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B004UBFXFC

Scribd, B&N, 24Symbols etc: https://books2read.com/u/3G2qPb

Google Play: bit.ly/EatenJG

Smashwords: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/50202

PAPERBACK:

https://www.amazon.com/Eaten-Japanese-Memoir-Indian-Prisoner/dp/1480034053/