Interview with Richard Crasta: April 5, 2008

The following questions—all except the final one, which is my statement on the book—were submitted by an online literary/news website, and what follows are the answers I sent them, very mildly edited.

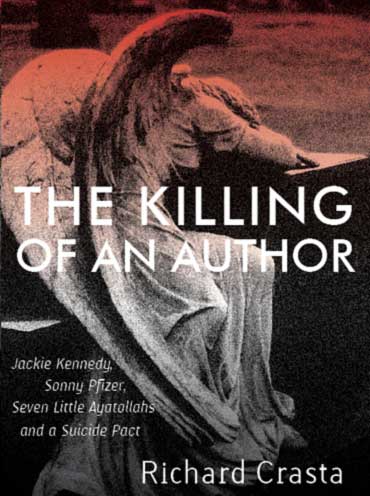

The inspiration for The Killing of an Author came while I was living in New York trying to sell The Revised Kama Sutra to American publishers. I was sending out literally hundreds of letters packed with raw emotion, pain, desire, anger, a feeling of injustice, a sense of history, of truth, of commitment, of the principles of the best literature and free expression. And I said to myself, “If I am going to have to waste so much energy trying to sell a book that is far better than the average stuff that they publish, then it is worth making a book out of my experience. All this writing and pain cannot have been in vain. This story cannot be hidden, must not be hidden, because others in my position will benefit from knowing what happened, how it happened, why it happened, and was it right, and what can be done about it. These issues need to be discussed and aired.” Thus was born a burning desire to publish this book someday, and never to let fear or petty self-interest stop the publication of it.

It is not a novel per se, because it is 100 % true in its narrative, or at least as far as I know or understand what truth is and am capable of being true—only four or five names have been changed, and hundreds of names are given straight and unchanged. It is a thriller because it takes you on a roller coaster ride that you would have to pay $39.99 for if you went to one of the amusement parks around Philadelphia . And that would exclude the $50 cost of transportation. I have had a few people tell me they read the book nonstop—including a friend who says he has never in recent memory read anything nonstop. That is thrilling news, that’s a thriller-like feeling. Thank you for acknowledging me as the inventor of a new literary genre . The inspiration has already been mentioned: experience, pain, a desire for justice, for meaning. Maybe, I thought, perhaps by writing this, I could begin to make sense out of this huge tragic story.

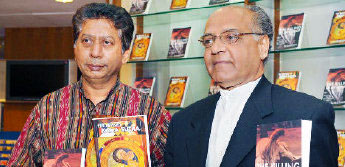

Michael F. Saldanha, retired Judge, Karnataka High Court, releasing the books The Killing of An Author and The Revised Kama Sutra, by Richard Crasta (left) in Bangalore

I am amazed and disappointed, for example, at the fuss we make and the newsprint and television time we devote to so-called wardrobe incidents in which one or two nipples are exposed around once a year in a country whose population possesses one billion nipples—two billion if you include the male contingent. Only one television channel, I remember while switching channels in my Delhi hotel room, and it was a Hindi infotainment-news kind of channel, repeatedly showed the actual nipples, while pretending to discuss the issue solemnly as if it was discussing the Iraq War; the other media reports, print as well as television, airbrushed them. To anyone who was born and suckled by a mammal, nipples shouldn’t come as such a shock; but for nipples, the human species wouldn’t exist, because nipples preceded the invention of feeding bottles and fake milk by about a hundred thousand years. I think this country, which has so many days, like International Litter-free Day, needs to observe an International Nipple Liberation Day.

Have you actually seen the order banning it? I haven’t, and don’t know if such an order ever existed. I would like to know if it is true, one way or another. I simply noted that certain booksellers had removed the book from the shelf, certain others had refused it, and one distributor had returned my entire list of books, in effect banning me, not just one book! I call it a ban when a book of mine that sold seventy copies in one Bangalore store alone, is refused display and stocking without any reason. Indeed, it is much worse: it is ball-less Ayatollahism.

The Revised Kama Sutra, of course. It has love, laughter, hope, desire, truth, women, sex, history, politics, social description, and so much else—nuclear physics too, if you look deeply enough. If only the publishers had been fair about that book—the kind of publishers, like Sonny Mehta, who could have granted me a mid-six-figure advance without blinking—I would be writing more such books, not having to fight the establishment, which is a thankless job. When the money didn’t come, my whole life exploded, and without family property, a trust fund, or major job-getting skills to fall back on, the process of writing and taking risks has taken its toll.

It was based on an essay, detailing my experiences of being typecast by Western editors as “non-Indian” because of my original name, Richard Crasta. Actually, the full story is not entirely explained by the essay, but in the narrative of The Killing of an Author itself, where the reason becomes abundantly clear. It ended up being a brief experiment, part-satirical, and more loved by my European publishers than by me. Obviously, it is an ex-experiment now. Pseudonyms have been a tradition among writers and actors for hundreds of years. Anyone has a right to change their name, to use a pseudonym, or to change their name back to what it originally was. It is a secondary and unimportant issue, except to intolerant fundamentalists and brownnosers of the Celebrated; what matters is our writing.

My childhood was marked by pain, deprivation, loneliness, and erotic repression (even thinking about underwear or private parts was considered wrong), and yet I also had an imagination, and a limited access to newspapers and books—mostly during the holidays—and from the combination of these two arose the desire to write, to tell the world my story. There was not much laughter in that world except at the rare Laurel and Hardy or Jerry Lewis movies, perhaps two or three times a year, and in the comics I borrowed from my friends during the school vacations. Perhaps this deprivation, and the balm that laughter is, brought that influence into my writing.

Not any one, and many different authors—and specifically, certain books by these authors–have been more influential at different stages of my life. Shakespeare, Henry Miller, Charles Dickens, Evelyn Waugh, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Don De Lillo, V.S. Naipaul, Salman Rushdie, to name a few.

A sketch by Mario Miranda of Richard Crasta

I cannot think of a specific influence, except that I was encouraged by a priest during my college days, when I was 16 years old, and that was the time I found I could easily win essay competitions and impress examiners with my writing style. I think the original inspiration came much earlier, from within, when I was ten years old and wrote an ultra-short novel, which would I would later understand to be a short and atrocious novella, justly destroyed by whoever did destroy it.

Three novels and a nonfiction book.

Travel, music, movies, company.

I have to find my support from within myself. At no time in my life could I have said that someone else’s desire or support for my writing was greater than my own unstoppable passion to be a writer; I would have done it regardless of the price, even if I had to sign away my life.

Writing in a cabin or house in the mountains, or overlooking the sea, in California , Cape Cod, Himachal Pradesh, or Hawaii , and never having to worry where the money was going to come from for the rent and my daily bread for at least the next five years.

I have written a brave book, and published it as I said I would, almost against all odds, a book that would take a huge endowment of balls for any writer in any part of the world to write. The book has been sent to around twenty reviewers, and three have so far reviewed it, with varying degrees of focus and concentration—but I congratulate them and their editors for their courage in any case. Khushwant Singh and The Week magazine have in effect declared that the book exists, and it has been baptized; therefore, it exists, it is a fait accompli. If the book does not reach bookstores and people, if it is secretly and effectively banned by a cunning and secretive coterie, and if it is not read, and if people are indifferent, it is India ’s shame, the people’s shame, and Indian democracy’s shame, not mine.

I’m delighted to hear from my readers or anyone with an interest in my writings. You can drop me an email by filling in the form below.

I will reply as soon as possible.