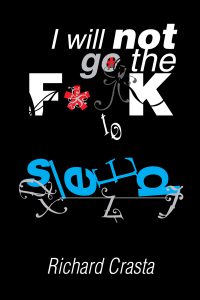

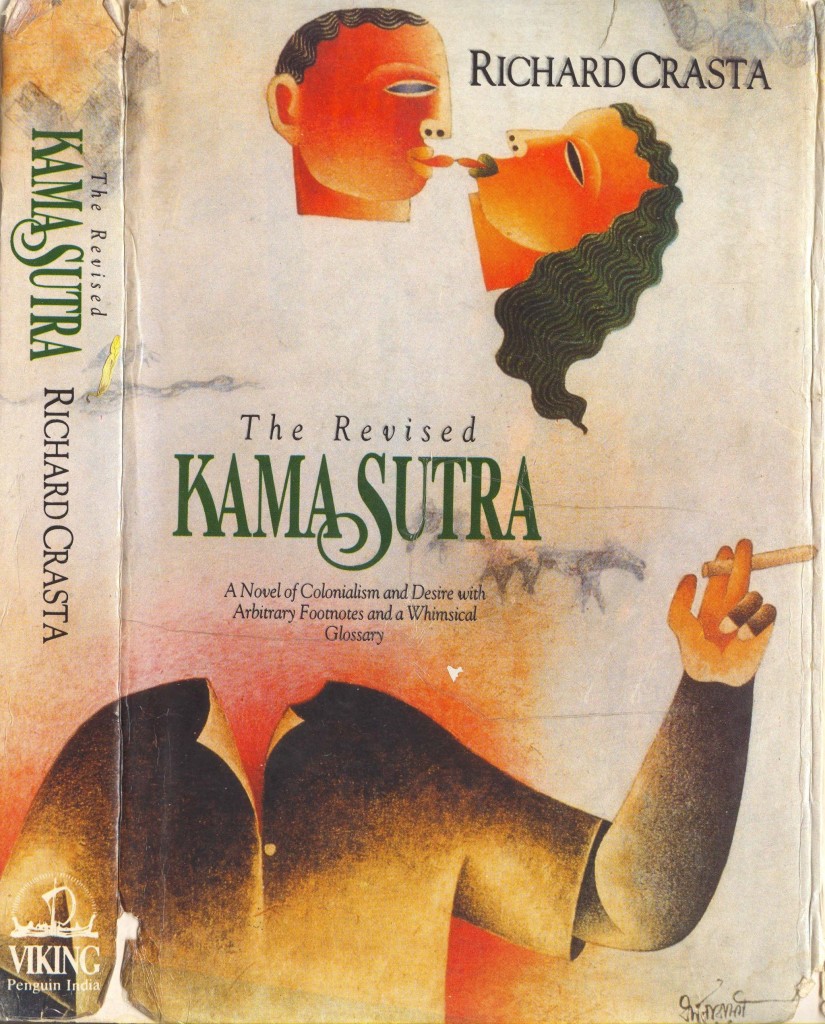

So how did that terrified and frail boy in the top right corner get to publishing this ballsy, boisterous, establishment-defying novel (see image on the bottom) 30 years later?

In a way, I never knew childhood at all, except for a few memories when I was 5, and a few summer holidays, and some games of ping pong and caroms in the boarding school. Adulthood and fending for myself, thinking serious, somber thoughts—it was thrust upon me at the age of 6. If I didn’t make sure to eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner, I went hungry. Nobody came after me asking me, “Did you eat? Are you okay?” Because the convent boarding house had around 80 boarders from Class I to Class X, and around two nuns and three ayahs or housemaids who functioned as part-time governesses to the children, but only minimally, only to remind, punish, and make sure no one had shit his pants and was trying to get away with it (we were so tightly fitted, in our short narrow bedbug-ridden beds, that there was not much room for smell, so a strong smell would be noticed by more than a few).

I remember the ayahs or housemaids, particularly a rather fleshy one who wore severely framed glasses, only in the role of cursing me for having wet my bed. I understand her now, that she was from the working class poor and probably overworked, and with little prospect in life, possibly condemned to be a spinster forever, and her reserves of compassion had been spent on herself, since others didn’t care too much about her.

You my classmates who used to go home to mothers and fathers and doting aunts and uncles and grandmothers and servant women, mothers who made sure you ate, washed, had a good appetite, and clean clothes, and enough time for both play and study: did you think of what it must have been for some of us to leave class and go “home” to strangers whose only relationship to us was a part-commercial accident? And that sometimes we were hungry, or felt underfed, or longed for something nice to eat, but didn’t have the courage to ask, or the hope of getting it if we did? And that sometimes we were beaten unjustly, but had no one to complain to?

Responsibility is adulthood. To be required to organize your own studying, home work, bathing, eating, shitting, and all that at the age of 6 is something that millions in poor countries experience (and my heart weeps for those who don’t even have schooling, must work as child laborers or slaves, or starve). But as a 6-year-old, I did not have the mental equipment or universal consciousness to compare my lot with children in far worse situations. I compared myself to my classmates, the majority of whom—say 17 out of 20—went home to real mothers and fathers or doting grandmothers. I remember a girl named Shaheen who had a horse-drawn carriage sent to pick her and her sister up for lunch, and then again after the end of the school day: I thought of her as royalty. Another girl named Latha had a car that would come to pick her up for lunch and drop her back.

In the holidays, I was under the overall guardianship of one of my father’s brothers, an affectionate man with an infectious and kind laugh, but a strict disciplinarian and very busy with his life and demanding business. Mostly he arranged for me to stay with my other uncles or my grandfather during the holidays. And it was instantly clear to me at these houses, when these uncles began to have babies, that I would (naturally, I realize now, it’s a basic law of life) never receive the same degree of love that they reserved for their children. That I had lesser rights, and a lower status, that I needed to watch my step, because I was their guest, I lived there by their will and command, and only so long as I was in their good graces. But they were relatively well off businessmen, and they ate well, and I always looked forward to mealtime in their homes, and the occasional trip to a restaurant where we could order a masala dosa; compared to it, boarding house food was punishment.

When I arrived at St. Aloysius Middle School for my Class VI, I must have looked a bit like the boy in the photo above, which was taken 3 months earlier. Five years later, the Class X photograph is evidence that I had been eating my mother’s food for the previous two years, and had bitten the skin of the apple of knolwedge. Class V was the low point in my life, because I was under the care of a terror of a devout, church-going, novena-obsessed woman, who sometimes starved me, put me out of the house for the night, extracted labor from me (forcing me to neglect school work), or punished me in other ways, and fed me inedible food. At that point, too weak to defend myself, I had learned that invisibility was the best way to stay out of trouble.

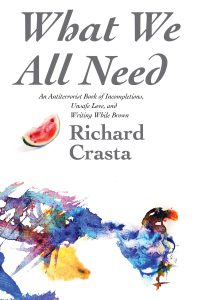

You who have started this Class X group, for which I am grateful because it jogs my sleeping and fuzzy memory: around half of you are blanks in my memory. And I was, then, probably unknown to many of you. Now, a handful of you have mentioned that, later, you used to read about me in the Indian newspapers (around the time that I published my first, second, and third books). But when I was in school, I was a cipher to most of you, because my father was not someone you had heard of, or who seemed rich. I was not Bus Company Rao’s son, or Tile Factory Pinto’s son, or Police superintendent Rahman’s son, so you didn’t need to fear me or know me. And because I was not physically strong, especially in the earlier years, and had learned to be invisible.

Also, I now understand and recall why I don’t know much about each of you and the incidents you talk about. It was not just because of the socio-economic class divide, but because my free time was taken up, for three out of five years, with acting in Father Rector’s dramatic productions (The Mikado, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Gondoliers), which he took seriously and passionately. When I was summoned and drafted, I didn’t have a choice: he was the Father Rector, which in those days meant dictator (at least to me). In retrospect, these productions enhanced my English vocabulary and my sense of humor, but as I mostly had small parts, I wasted most of my time hanging around, without a book to read, and didn’t get to exercise my body, so remained weak. Probably 150 hours a year and 450 hours in three years were spent on these dramatic rehearsals and performances, time in which I could have read 200 books or/and played with you and gotten to know you better.

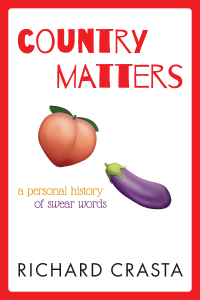

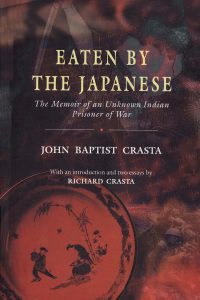

So even when I should have been free, after class hours, I was rarely free. In the ninth standard, we lived in a house without running water, and I and my elder brother had to help my Dad (who had just retired from a 30-year service in the army, including 3.5 years of being a Japanese POW–I have published his memoir, Eaten by the Japanese) draw water from a well without walls, then drag the buckets to our home 70 meters away. And in the tenth standard, I had already sprouted pubic hair, and my attention was now dragged, biologically, in a different direction.

But before then, I had yet another time suck and life suck to deal with. I had been religiously brainwashed in the convent and in the boarding school, and during St. Aloysius’s annual retreats, and intent on becoming a saint: an absurdity when I look back at it and consider how un-saintly my life has been since then. But I spent loads of time voluntarily praying, in addition to the compulsory prayers, and I even believed that not hitting back when someone hit me would increase my heavenly merit—whereas I now know that one of the best ways to tackle bullies is to hit back and inflict some damage on them. It was only in the Pre-University Class, when puberty was raging inside me, that my suspicion solidified into the belief that the religion I had been taught was mostly b.s. and religiously obsessed people had been some of the most unjust people in my life.

A handful of you I was closer to (one of you explained to me the constellations), having visited your homes, and a few other boys I remember (random memories):

Cyril Pinto, who was almost permanently amused (his eyes smiled even when his face didn’t), and who died suddenly some 10-15 years back and was with me in VI and VII grade. Vincent D’Souza, who was with me since Marjil and had a haunting voice and sang Hindi film songs at various college functions, and also acted in Konkani or Kannada sketch comedies. Gerard Pereira, who also seemed permanetly amused, and had a talent for being friendly to Cyril, who had loads of currency notes in his well-starched pockets (his clothes looked like an advertisement for Surf washing powder—after the washing), and who shared sweets and bhends with him. Gerard also had loads and loads of comics and story books, which I borrowed during my summer holidays, sometimes reading a few right there in his house.

Wilfred had a very strict father who seemed to strike terror in his heart—I felt sorry for Wilfy when his father came to take him home from the boarding after he had committed some disciplinary sin I do not know the nature of.

These are just some scattershot memories of many, but some of them have been wiped out by the Vesuviuses in my life.

So, having missed part of my childhood, I think I understand why I am not as fully an adult now as some of you. Which, of course, depends on your definition of adulthood–which, I think, has been greatly overrated.